Olaf Merk is a Ports and Shipping Administrator at the International Transport Forum of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). Over the past decade, Merk has led several research investigations that have uncovered problems with large container ships, and here's what Olaf Merk has to say about it.

Of course, Merk is a loyal big ship opponent. This article only represents his personal views and does not represent the views of Xinde Marine.

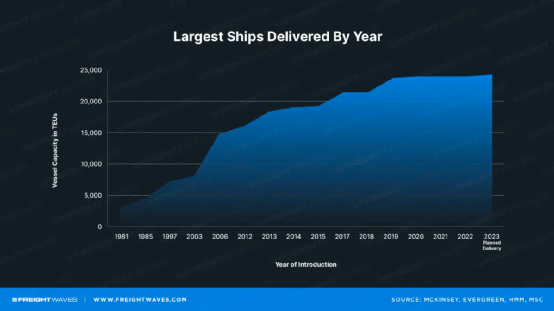

Why did ocean carriers continue to build larger and larger ships throughout the 2010s, even as ocean freight rates and trade volumes declined?

Merk: "I think building bigger ships is an option for the carriers to drive some of their competitors out of the market, but I also think many carriers can't keep up with that competition.

"In the case of Maersk, it may seem a bit paradoxical that the company chose to build large ships before trade had resumed, but I think it was also intentional because some of their competitors were in financial trouble at the time, so This is their original plan.

"Of course, things didn't go exactly as they had planned. That's where the shipping alliances come into play, and some shipping companies have decided to join the alliance and start ordering new ships with alliance partners. Eventually we saw round after round of rounds of consolidation, mergers, acquisitions and bankruptcy, while all the top carriers work more closely together."

"In the end, the shipping market has become a much tighter market with fewer players, and I think that's their intention."

Ships are getting bigger, and ports, especially in the U.S., have not kept up with the trend toward larger ships. From a global perspective, what is happening right now? Will giant ships become more economical if ports can maintain scale and innovation?

Merk: "When container ships get bigger, port infrastructure may not keep up with demand, especially in the US. Ports need to upgrade and innovate, and if shipping companies need to pay for port and terminal adjustments, they won't be able to keep up. Economical. The truth is, they don't need it, so that's why the giant ships have been economical so far."

"The port felt that the extra investment made was not recoverable, and if the carrier had to pay for bigger cranes or dredging work, then there would be no point in going bigger. We also mentioned this in our 2015 report, we calculated Looking at the cost of the entire transportation system, it turns out that the cost of the larger container ship is greater than the cost savings of the carrier."

"Really big ships will affect all ports around the world. Let's say big ships are going to sail between Asia and North West Europe, then all the focus will be on those ports and how they adjust to Hamburg, Antwerp and the EU The dredging that port expansion brings to them. If ships are going to cross the Pacific, that means a series of port upgrades like North America."

So what is the situation facing developing countries other than European and American countries?

Merk: Similar challenges are faced in many parts of the world. The ability or willingness to accommodate giant ships are two different things. For example, we looked at the port of Buenos Aires in Argentina and some other Latin American ports, and we found that they didn't make a lot of port changes. "

"In this case, the carriers have adapted some of their ships to specific ports or water depths. In fact, they have developed a specific Latin American ship for the route."

"In general, most ports don't have many options and they are also in competition with other ports in the same region. Carriers will threaten to go to another port unless the port invests."

So why are some countries still willing to attract carrier companies through tax incentives and other means?

Merk: "It brings to mind the issue of taxation, like in various small counties and towns in the United States, the states are subsidizing Amazon to build distribution centers. The problem is that Amazon will create sub-locations whether they are subsidized or not. For ocean shipping The same is true for people, the carrier will go regardless of whether there is a subsidy everywhere, but I think the difference with Amazon's mechanism is that this may not be a monopoly, but an oligopoly. On the one hand, several carriers form an alliance, It represents a significant portion of the traffic at certain container ports. The flip side is that these ports have to compete all the time if they want to continue to be big ports."

Ask port supervisors what kind of ships they would like to see in port, and their truest answer would be: "Actually, we prefer two 12,000TEU vessels to one 24,000TEU vessel, Because these very large ships have too little flexibility to provide services.”

A few years ago, China was not quite sure that mega ships were a good idea and had not really invested in large ships, with the port of Shanghai saying the ideal size was 14,000TEU.

Merk said: "At that time, the European Commission had talks with China on this matter, but there was no consensus. The European Commission still insisted on the process of large-scale ships, which they believed was in their interest, but I think they should think about if the system What will happen to the port, to the logistics system, to the transport network? I think that should be a consideration.”

Merk: "There are a lot of secondary and tertiary ports and actually the big carriers don't go there, so they're not interested in those ports in a way so that the ports can come and go according to the needs of the regional economy. Developments are made, not arranged according to the wishes of a few global carriers."

"Most ports have to adapt to the needs of the carriers and change to another type of terminal, of course it's always difficult, most ports don't say 'enough, we're going to get out of the big line's container business', in most cases down, these ports are more like victims of the global game.

There are three major alliances of container shipping companies, why are ports not allied?

Merk: "Actually, some ports in some places have merged, like Seattle and Tacoma, and some Japanese ports have merged. Recently in Belgium, Antwerp and Zeebrugge have merged. Ports have also emerged Some cooperation, but of course much less than in the case of liner companies.

"We looked at all the corporate agreements between the large carriers and found that Abocean carriers not only cooperate within alliances, but also across alliances.out a quarter of these corporate agreements are in the top 10 that are not part of the same alliance Between the carriers. The conclusion we draw from this is that it is alliances that dominate the shipping industry, but in reality there is a lot of connection and cooperation between the carriers in these alliances.

"Obviously, none of the ports are strong enough on their own to really stand up to these carriers. So there needs to be some kind of cooperation between ports if it is to be more in the public interest than the private interests of the carriers."

Merk previously published a commentary on FMC's fact-finding market analysis, in which it referred to the Herfindahl-Hirschman Index (HHI), a composite index that measures industry concentration. The "Horizontal Consolidation Guidelines" in the United States defines that a market with an HHI value greater than 2500 is a highly concentrated market and should be avoided.

Merk said: “Our research found that 15 of the 33 maritime trade routes to and from North America have HHI values above 2,500 points and can therefore be considered highly concentrated. However, these traditional indicators do not take into account The effect of alliances and other cooperation between carriers, so such high HHI values are still underestimated. To correct for this, we calculated revised HHIs, which turned out to be much higher than before, for example, on transatlantic routes Above, the traditional HHI value is around 1500, and the revised HHI is 2500, indicating high concentration.”

“On many routes, there are hardly any independent carriers, and on the transpacific route, the independent carrier market share of about 8% in 2021 is significantly lower than in any previous year.”

What is the real role of these alliances? Will this lead to higher freight rates? Will this lead to lower efficiency?

merge Want these big ships. If the ships are much smaller, there's basically no need for an alliance."

"Imagine having 10,000TEU instead of a 24,000TEU vessel. Well, it's a lot easier for a single carrier to connect to a global network, which they can't do at the moment because they don't have A facility of this size."

"But I think the biggest impact is on the public infrastructure, the ports are basically playing against each other and the taxpayer pays for it, not the carrier. The theory is that the carrier pays port dues or something like that, but if A closer look shows that the carrier doesn't actually pay the full amount, and a lot of it actually comes from public funds."

"So what do taxpayers get in return for paying that? In reality, the transportation system hasn't gotten better, connectivity and reliability have not improved, especially over the past few years. Obviously, taxpayers don't know this. A little bit, but why would they pay for something that doesn't actually improve? That's a big question. Of course, it has to do with this increasingly powerful position of the carriers because they can get the ports or the government to pay for it."

Shipping giant's record profits and meager tax bill

Merk: "We've seen a huge increase in freight rates, of course it's hard to prove whether it's related to carriers canceling voyages and raising freight rates. Many competition authorities are looking into this issue, whether it's really the cooperation between the carriers. the situation we are in now."

Merk said: "Looking at these blank sailing times, and the period in which these blank sailings occur, blank sailings appear to be much longer than might be reasonable, with a lot of capacity sitting idle, with a lot of sailing empty in the spring and summer of 2020. Coming out, freight rates started to rise in May and June 2020, but it wasn't until September 2020 that capacity actually returned to normal.

"This is just one example, there are other situations where I think competition authorities can really look at what's going on and wonder if all the cooperation they've allowed carriers to have is also having an impact on the supply chain that is not in the public interest. "

Merk said: "I've seen some statements from the competition authorities and they've done some public inquiries. But so far their explanations for some situations are simply too simplistic and inaccurate, but the authorities still seem to believe them. ."

Merk also touched on some areas of interest, saying: "Vertical integration is an issue and many carriers are now also active in many other parts of the transport chain, such as in terminals and freight forwarding, logistics, etc."

"The other point is that the carriers have really made a lot of money in the last two years, they've hit new highs when a lot of other industries are trying to survive, but it's interesting that a lot of these shipping companies don't pay a lot of taxes. Now they These record profits are being made, but the average tax rate is about 2%."

"There's also the issue of decarbonizing the shipping industry, which uses the dirtiest fuels in existence, and whose greenhouse gas emissions are basically comparable to countries like Germany or South Korea, where shipping can reduce a lot of emissions," Merk said. But for now, the process is not very fast, so there is still a lot of work for the shipping industry."

Previous:Backlog of container ships outside U.S. ports, more than $40 billion worth of cargo waiting to be un

Next:Port of Long Beach container backlog crosses red line